Corey Drieth was born and raised in Northern Colorado. He attended Colorado State University in Fort Collins where he received undergraduate degrees in Philosophy/Comparative Religious Studies and Studio Art. After serving as the Critic and Artist Residency Series (CAARS) coordinator for CSU’s Hatton Gallery, he attended graduate school at the University of North Carolina and received an MFA with a thesis in Drawing/Painting in 2004. Before joining the Visual and Performing Arts Department at the University of Colorado in Colorado Springs in August 2007, Drieth taught studio art classes at CSU, the University of North Carolina and the University of Virginia. His work has been exhibited throughout the country, including San Francisco, Chicago, Albuquerque, New Orleans, Washington DC and New York City.

Corey Drieth was born and raised in Northern Colorado. He attended Colorado State University in Fort Collins where he received undergraduate degrees in Philosophy/Comparative Religious Studies and Studio Art. After serving as the Critic and Artist Residency Series (CAARS) coordinator for CSU’s Hatton Gallery, he attended graduate school at the University of North Carolina and received an MFA with a thesis in Drawing/Painting in 2004. Before joining the Visual and Performing Arts Department at the University of Colorado in Colorado Springs in August 2007, Drieth taught studio art classes at CSU, the University of North Carolina and the University of Virginia. His work has been exhibited throughout the country, including San Francisco, Chicago, Albuquerque, New Orleans, Washington DC and New York City.

What inspired you to become an artist?

To be honest, I am not sure how to answer this question. I say this because I think I’m kind of hardwired to be an artist, and knew this from a very early age. When I was about four or five years old I remember telling myself that I was going to be an artist, and that I was going to be a really good one! So, I was determined from the start. I loved drawing and looking closely at things and it just seemed natural to make as a response to the world around me, as a way of understanding it, participating in it, sometimes even as a way of escaping it. So, it doesn’t feel so much like a choice as a way of being. But as a child I do remember being really inspired by specific images. Two that come to mind are John James Audubon’s Northern Hare (Winter) and Juan Sanchez Cotan’s Still Life with Quince, Cabbage, Melon and Cucumber. I saw pictures of both pieces in an old set of encyclopedias and I still remember how much they affected me. I couldn’t explain why. I probably still can’t today. But I knew they were special and I wanted more.

OK, so now I’ll try to answer your question more directly: Like many kids who are interested in art, I was also inspired to be an artist by the images that populated my world. For me that meant old Looney Tunes cartoons, photographs in my Dad’s hotrod magazines, religious imagery in my grandparent’s house, comic book illustrations, ads on TV, and the occasional fine art book, etc. But I had no idea as to what it took to become an artist, professionally speaking. It wasn’t until my mid-twenties, when I met my friend and mentor Bill Wylie (who currently teaches photography at the University of Virginia) that I began to grasp what it means to build a life as an artist. He showed me how to educate and expand my sensibility, how to trust and be true to myself as an artist, and how to create a professional path based on my character and interests. I had other teachers who helped me along the way as well, but Bill’s friendship was (and still is) profoundly influential. By way of it, and by way of his generosity, I could see first-hand how a person ‘becomes an artist.’

What is your ideation process? What does creativity look like for you?

As I mentioned above, I feel most at home when I pay close attention to the world and when I imaginatively engage with it. I am constantly taking pictures of things that interest me, and scribbling down thoughts for new projects in my sketchbook. Although I am a slow reader, I read a lot, and books influence me a great deal as well. I primarily read nonfiction, about nature, religion, and art, and I like to read poetry too. So, many of my ideas for paintings come out of what I encounter in books. I openly embrace the idea of being influenced and I work best when I am responding to other images, or a given set of circumstances (in a way similar to many photographers). So, when I paint on wood, I am responding to the structure of the grain, trying to discover a meeting place between my vision and what is given. For me, this is what creativity looks like. I see it as investigation and discovery – a call and response – more than anything. It is a perceptual process, taking place between the outside world and my interior life. Coming up with an idea, applying it via materials, and evaluating my success based on how much the result mirrors the original idea is not very satisfying to me. I am much more interested in the revelation that happens during process, consciously setting up a limited set of circumstances (materials and design language) and then exploring within it. And revelation only occurs when I let go of intention enough to be open to discovery, or when I fail enough times that I become so desperate as to be open-minded. Either way works.

What is your daily routine?

During the summer, when I am not teaching, I try to set a schedule that keeps me balanced and productive. But that can be challenging sometimes, especially here in Colorado where the beauty and freedom of the outdoors constantly calls. But when I am successful it looks like this: In the morning I read a little and exercise (hike, run, ride a bike), meditate, and do errands when necessary. Then, after an early lunch, I work in my studio until dinner. Then I have a cocktail, read a book, and/or watch a movie. Ideally, I do that six days a week, but all bets are off if I have a deadline.

In your undergraduate program at CSU Fort Collins your concentration was in pottery, then during your MFA degree at the University of North Carolina you shifted focus to painting and drawing. Can you speak about what led you to this shift and do you still find influence from pottery in your painting and drawing practices?

My academic history is a little deceptive in that my resume makes it seem as though I studied pottery before painting and drawing. But the truth is I have always made paintings and drawings and came to pottery late. In the process of trying to figure myself out, I went to college two separate times and have two different undergraduate degrees. The first is in comparative religious studies (with a minor in painting) and the second in pottery. It’s a long story and I won’t get into it too much here, but for a while I lost faith in myself as an artist and didn’t believe I would ever be able to make a powerful painting. But after having met Bill and having encountered a pot made by the artist Richard DeVore (who taught at Colorado State University until just before his death in 2006), I knew I had to go back to school to get my BFA. Until that time, I had little interest in pots. But something about his work woke me up in the same way as I described above. So, I re-enrolled as an art major in order to study with him. It was the best decision I have ever made. It led to so many impactful experiences, including becoming a part of a really vital art community, the start of my professional life in the arts, and ultimately to graduate school and my career in teaching.

I moved to Chapel Hill, NC for my MFA two years after finishing my degree in pottery and my intention was to continue the work I had been making prior. At the time I was creating mixed media, vessel-based installations and sculptures. Clay was at the center of that work, but it really was exploring the meaning of vessels in an expanded way. I got off to a strong start but soon seized up; I wasn’t making work that had the clarity and depth that I was craving. After a lot of soul searching, and paying attention to the things I most loved to look at and think about, and by way of a great deal of support from my community, I found my way back to painting. In that pivotal moment I allowed myself to make paintings in a way that I had often thought about but didn’t think could be viable as art, and the world opened up. I haven’t looked back since.

In terms of how pottery has influenced my painting, I think it actually freed it. Because of my background in that craft tradition I was able to start to see paintings not only as stylized representations of the world, but as craft-able objects. By this I don’t just mean the technical craft of applying paint to a support. I mean that the literalness of paintings (their materiality and overall physical presence) started to intrigue me and I became fascinated by how they could be experienced both as windows to the world AND as objects in their own right. Further, one of the major formal issues we discussed in the pottery program at CSU was the surface/object relationship, or how glaze reveals and/or conceals the body of the pot. This led me to think about how the material support for a painting could play a major expressive role, and not just function as a default ground in the way that white primed canvas usually does. Finally, I think the intimacy and ritualistic use of pots also influenced how I think about my paintings. I use scale and economy to create work that requests intimate engagement and I think that comes directly out of working with functional clay vessels.

What do you value most about your creative communities?

I value the common sense of purpose, the empathy we have for one another, and the support we give one another. We share resources and ideas, we inspire each other, and I love being challenged by my creative community to think more broadly about art and the world. As a profession, art is both extremely satisfying and challenging. Opportunities are not abundant and are very competitive, and artists often work in solitude a great deal of the time. Plus, in our culture it is often seen as an eccentric and not very utilitarian (and thus not very valuable) career. So, having a community makes it much easier to sustain my practice. When I became a part of one I didn’t feel so lonely, odd, and isolated. It was as though I found a family who shared a similar way of being in the world, which helped me feel much more at home in my own skin. I would say that my community enriches my life and helps give me license to live how I want to live.

How does art navigate the spaces that exist between people? How do you navigate the spaces that exist between institutions (like museums/galleries) and artists?

I think some of my answer to this question can be found in question #5 above. But to expand, I believe really good art inspires a rich array of responses and leads to conversation. It mirrors and amplifies the world around us and asks us to look more attentively, think more critically, to examine our values. Fundamentally, I think it is art’s nature to create communities, whether they be economic, cultural, political, religious, and/or personal ones. When we actively and critically reflect upon art, we breathe life into it. The more we collectively do so (which doesn’t necessarily mean coming to any kind of strict consensus about what it means, how historically significant it is, or what its market value is), the more we give it vitality. As a consequence, to be a serious professional artist means that you have to navigate the spaces outlined above all of the time: it’s part of the job description. I do so personally by trying to make the best art that I can…’best’ meaning ‘most evocative.’ This part of the job takes place in the studio and I fundamentally believe that the art you make there is ‘the horse that drives the cart’ and that everything else is in the cart. From there, I try to be the best artist that I can be, meaning that not only do I have complex, evocative work to present, but that I am dependable, adept at talking about my work, and easy to work with. Last but not least, I do this by trying to be the best teacher I can…best meaning I try to be as informed, clear, demanding, and supportive as possible. I don’t always hit the high mark with any of it, but I can honestly say that I try my best.

If you could collaborate with anyone in time and space, who would it be, and why?

While there are countless artists around the world and throughout time who have inspired me and who I would love to meet, I would rather give a more realistic answer to this question. I say this because I think the possibility of actually collaborating makes it much more intriguing. I don’t collaborate often, but in the last few years I worked on a couple notable projects. First, Jonathan Dankenbring (who works at the FAC as its Exhibition Designer/Preparator Manager) and I worked together on a show entitled ICONCOLASM. This wasn’t a collaboration in the traditional sense in that we didn’t work on pieces together. Rather we created our own work based on an agreed upon theme and shared aesthetic sensibility. I also recently completed a year-long project with Bill Wylie entitled THIS:THAT which was based on a shared love of the work of Italian artist Alighiero Boetti. For this project we created a material score and a set of rules and then went about individually responding to that score over the course of eleven months. The show debuted in Virginia last October and is scheduled to be exhibited here in the fall of 2021. We are currently working with art historian Dr. Katherine Guinness on a catalog for that exhibition that we see as a part of the on-going collaborative nature of the project. Both of those projects have been really satisfying, especially because I haven’t had to compromise anything about my process or vision, which is almost impossible for me to do. In the future I can see myself collaborating with former students in similarly open ways. One particular idea I have would be curating an exhibition exploring the intersection between spirituality, gender, and identity. I have a number of students who have made really exciting art within this vein recently and I think it could make for a very interesting project. Locally, they include Ashley Anderson, Jem Brock, Su Cho, Jasmine Dillavou, Em Ducharme, Seth Edwards, Christine Flores, and Martha Wheeler.

How is your studio practice responding to our current moment?

Since the pandemic hit and since you sent me these questions, the ‘current moment’ has quickly changed and become so much more complex. In addition to the rapid spread of COVID-19, we have seen the dramatic rise of human rights protests around the globe, specifically those responding to violence against Black communities here in the states. While there has never been a shortage of suffering at any time in human history, there is a collective urgency to this moment that feels unprecedented. This urgency requires that all of us honestly and courageously examine our lives, and to act. As an artist, my primary way of being in the world is through making art, and in times like these the necessity and efficacy of that practice sure comes into question. At least it has for me. At this point, I am unsure as to how to exactly respond in my studio. I vacillate between making art that is critical of our culture, that exposes the confusion, fear, and hate that seems to be driving so much of the willful ignorance and violence, and making art that celebrates why life is worth living to begin with. So, I am trying to do both.

That being said, I do think the quarantine has created a situation that offers us time to reflect; the isolation, while psychologically and emotionally difficult, offers opportunities, and I am responding to the current moment in other ways as well, ways available to all of us. It is so clear that we cannot let this moment fade and that it needs support from as many people as possible. If these incredibly painful times are to have any meaning, we cumulatively must be committed for the long haul to making the world a better place. And that is where I think art can have its biggest impact. I believe protests can light a fire that demands an immediate response. When effective, they can lead to institutional change (policy, law, etc.). Art (the creation of meaningful images) tends to work more slowly. It can undress old, oppressive cultural values, while at the same time offering up newer, more inclusive ones. The changes it engenders tend to occur on a deeply personal level. And they often work together, as they have during the Black Lives Matters movement. Both forms of response are necessary if we are to work towards a healthier, more just and equitable world.

What do you hope that people take away from your work?

By way of answering this question, I think I will offer a version of my artist statement:

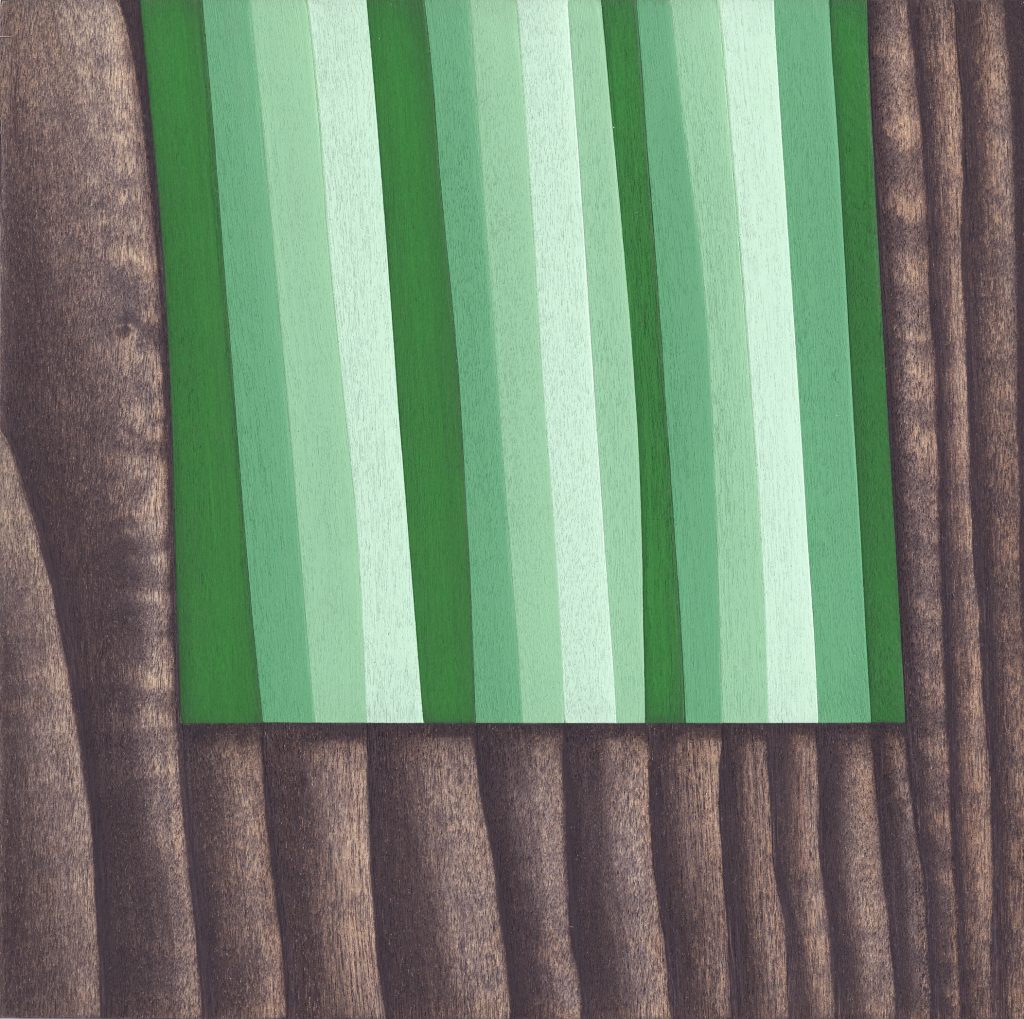

“For the past fifteen years I have spent almost all of my time in the studio making delicate small-scale abstract paintings on unprimed poplar panel. Inspired by daily life, art history and religious traditions such as Zen Buddhism and Quaker Christianity, this work explores contemplative spiritual experience. Like many people today I want to define my own spiritual path and I do so by borrowing from multiple theological, literary and artistic precedents. Subsequently, my goal is to create an iconography that is both deeply personal and highly evocative; I want to make lyrically poetic objects that are simultaneously intimate, mysterious, and expansive. More specifically, I am interested in the square as both a design element and a historically sacred principle and the act of exploring these ideas via painting has become the center of my spiritual practice.

Ultimately, I believe that experiences of subtle structural beauty can be incredibly valuable. Because they require quietude during a time of de-humanizing speed, clutter and noise, they serve as both a foil to the frenetic activity of contemporary life and as a method of sustenance within it.”