Decades before Katharine Lee Bates penned the famous words of her poem Pikes Peak in 1893, artists working in the European academic traditions were depicting the sublime grandeur of the Pikes Peak region. Colonizers of the Ute, Arapaho, Cheyenne, and other native lands sent tales of the rugged, dramatic scenery of the West back East, compelling artists such as Harvey Otis Young and Hamilton Hamilton to explore as well. The natural landscape of spacious skies, amber waves of grain, and purple mountains majesty of which Bates wrote, and would later become the famous anthem America the Beautiful, provided ample inspiration to late 19th and early 20th century painters. By the early 20th century, Colorado Springs was a popular tourist destination and a celebrated place for healing. Known as “Little London” largely due to significant British financial backing, this nickname also represents a desire for the city to create a cultural landscape mimicking established cosmopolitan cities. The Broadmoor Art Academy was born in 1919 from these expressed ideals and soon attracted students from across the country to immerse themselves in the landscape. The Broadmoor Art Academy shifted in name and facility to the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center in 1936, but the ongoing commitment to art education remained a pillar of the institution. The subsequent years were unprecedented in terms of artistic production. Informed by modernism and abstraction, creatives such as Mary Chenoweth and Robert Motherwell challenged traditional expectations by producing works that were on the leading edge of the contemporary American art scene. A century after the founding of the Broadmoor Art Academy, we celebrate the ingenuity of the artists and patrons who helped to shape the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College into the fine museum, performing arts theatre, and art school it is today. Through these works, created by exceptional visual artists over the course of 100 years, we can witness the dramatic shifts that have occurred in the physical and artistic landscapes of the Pikes Peak region. As Colorado Springs continues to grow, so does the importance of a strong cultural identity. We are proud to have been an early and ongoing participant in this endeavor and strive to embrace the many avenues toward a doubly inclusive and dynamic FAC for all.

Image above: Ethel Magafan, Meadows in the Valley, unknown date, oil and tempera on untempered masonite panel

Exhibition Highlights

Shifting Landscapes of the Pikes Peak Region

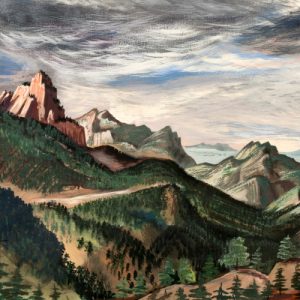

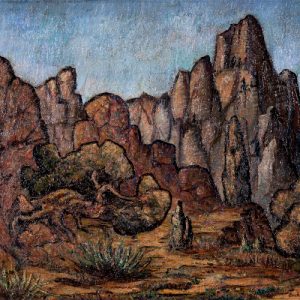

Katharine Lee Bates’ famous 1893 poem, Pikes Peak, captured the sublime grandeur of the Pikes Peak region. Colorado’s natural landscape of spacious skies and purple mountains also inspired artists, such as the painters Harvey Otis Young and William Henry Bancroft. In turn, their paintings spread knowledge of the beauties of Colorado to audiences across the country.

In the early 20th century, Colorado Springs became a popular destination for sight-seeing and healing. The city was known as “Little London” due to its cosmopolitan cultural landscape (and the significant British support of its railroads). Artists from across the country travelled to Colorado Springs, drawn by the scenery as well as the vibrant Broadmoor Art Academy (BAA). By 1936, when the BAA became the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, Colorado Springs was a nexus for innovative American art.

At the same time, the early 20th century was a period of tremendous turmoil. The work made by BAA teachers and students reflects the impact of two world wars, the Great Depression, and social and technological upheaval. Artists hold a mirror to our times, and the art of Colorado Springs reflects the tumult as well as the opportunities of the 20th century. Through 100 years of art in the Pikes Peak region, this exhibition explores a shifting social and artistic landscape — one that remains influential for artists today.

Shifting Perspectives

Indigenous peoples, including the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Ute, have lived in the Pikes Peak region for thousands of years. Motivated by Manifest Destiny (the belief that expansion westward was both inevitable and divinely mandated), white settlers arrived in large numbers after the 1858 discovery of gold in Colorado. Native American populations were displaced and decimated as a result. The Western landscapes on view here convey Manifest Destiny by showing the land as unoccupied and available for settlement.

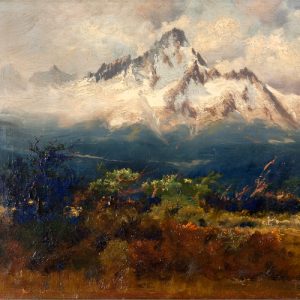

Mt. Sneffels, San Juan Mountains, Colorado (detail)

Charles Partridge Adams (1858–1942)

On view in eMuseum

Untitled (Landscape) (detail)

John McClymont (1858–1934)

On view in eMuseum

The Broadmoor Art Academy

Established in 1919, the Broadmoor Art Academy (BAA) taught artistic techniques in the European tradition. Often focusing on realistic, even idealistic, representations of nature and the human form, academies, such as the BAA, imported celebrated artists as teachers. John Carlson and Robert Reid, the BAA’s first instructors, brought New York academic sensibilities to the Rocky Mountain West.

BAA artists Birger Sandzén and Willard Nash taught the language of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, harnessing vibrant colors in rough, divided brushstrokes to depict the environment. Regardless of their personal styles, all of the BAA artists were inspired by the clear air and dramatic scale of the Pikes Peak landscape.

Shifting Perspectives

As a teaching academy in the European tradition, the BAA embodied and reflected structures of privilege. Teachers from the East, such as Randall Davey, commanded high fees. Female teachers had lesser status and pay. For example, in the annual exhibition of BAA student and faculty work, women artists comprised half of the participants. However, male artists commanded prices more than twice those of female artists: on average, $233.42 for a piece by a male artist versus $86.74 for a female artist’s work.

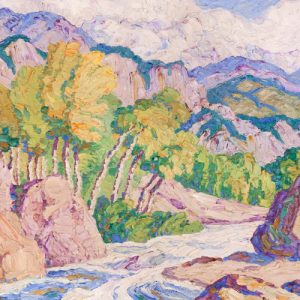

Mountain Stream, Big Thompson Canyon (detail)

Birger Sandzén (Swedish, 1871–1954)

On view in eMuseum

Moonlight, Garden of the Gods (detail)

Robert Reid (1862–1929)

On view in eMuseum

Early Morning Cripple Creek, Colorado (detail)

Ernest Lawson (1873–1939)

On view in eMuseum

The Fine Arts Center

In 1936, the Broadmoor Art Academy became the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center (FAC), a multidisciplinary institution envisioned by Elizabeth Sage Hare, Julie Penrose, and Alice Bemis Taylor. During the Depression, American Regionalism and Social Realism emerged as art movements committed to representing the everyday working-class experience. With progressive painter and printmaker Boardman Robinson at the helm of the art school, the institution gained national recognition. In response to the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted New Deal arts policies that afforded artists economic opportunities, often in the form of mural commissions. FAC instructor George Biddle helped conceptualize Roosevelt’s policies. In a letter to Roosevelt, his childhood friend, Biddle wrote, “the artists of America are conscious as they have never been of the social revolution that our country and civilization are going through; and they would be eager to express these ideals in permanent art form if they were given the government’s cooperation.” The FAC produced many accomplished muralists: between 1936 and 1940, artists affiliated with the FAC won commissions for 60 murals, including the Tabor Utley and Archie Musick paintings at the Colorado Springs City Auditorium.

Shifting Perspectives

In 1913, the provocative New York Armory Show introduced European modernist styles such as Cubism, Constructivism, and Futurism to American artists. However, still reeling from the Great Depression, many WPA-sponsored artists remained committed to social realist styles and agendas. Rather than rebel against the Establishment, WPA muralists used their state-sponsored public platform to capture and codify American identities for future generations.

Mountains (detail)

David Fredenthal (1914–1958)

On view in eMuseum

Don Quixote And Sancho (detail)

Boardman Robinson (1876–1952)

On view in eMuseum

Austin Bluffs (detail)

Archie Musick (1902–1978)

On view in eMuseum

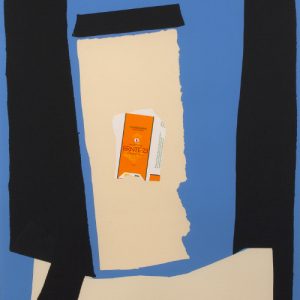

From Representation to Abstraction

During and after the World Wars, many European artists fled to the United States, bringing their modernist sensibilities with them. These international influences soon became evident in the work of mid-century artists in the Pikes Peak region.

In these paintings, we witness a striking transition from traditional to modern styles, revealing the influence of artists like Pablo Picasso and Jean Charlot. Figures and landscapes deconstruct into their essential components: form and color. Ellen O’Brien and Ethel Magat an abstracted the landscape using Cubist influences and vibrant color. Notice how abstract artist Mary Chenoweth, an influential Colorado College professor, was inspired by the colors (ochres, greys, and browns) and shapes of the regional landscape.

Shifting Perspectives

Abstraction was not a European invention. European artists such as Pablo Picasso and Paul Gauguin found inspiration in abstract designs from African, Oceanic, Asian, Islamic, and Indigenous cultures. Though these appropriated motifs are commonplace in European art, artists from the originating cultures are often completely excluded from the narratives and canons of Western art.

Summer Light Series: Harvest in Scotland (detail)

Robert Motherwell (1915–1991)

On view in eMuseum

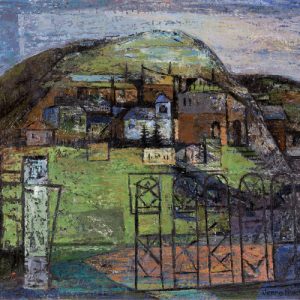

The Dark Village (detail)

Jenne Magafan (1916–1952)

On view in eMuseum

Forms from Nature (detail)

Ellen O’Brien (1922–2013)

On view in eMuseum

Presented as part of Pollinate: Biennial Arts Collaboration, exploring the theme of TIME across southern Colorado, April 1-8, 2019. More Info